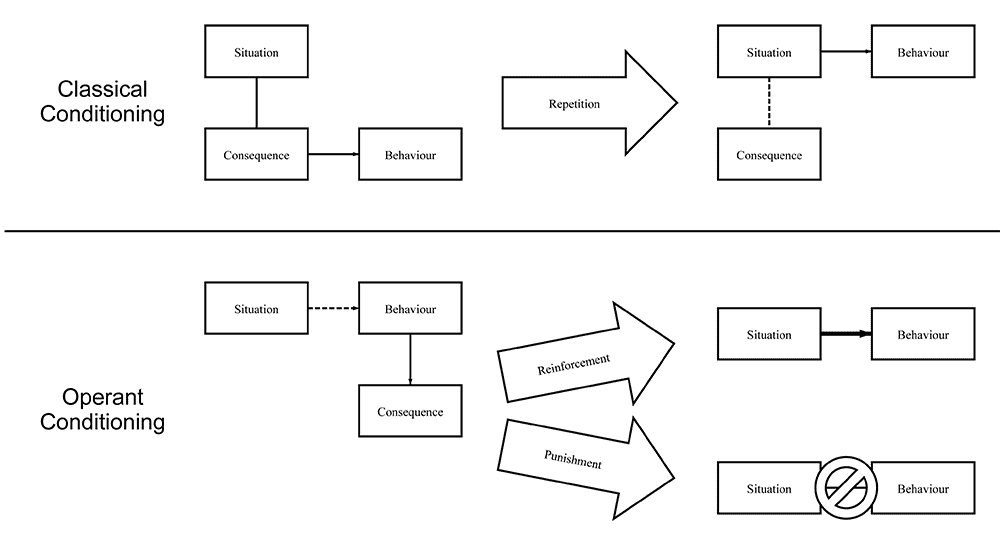

Classical conditioning and operant conditioning are two fundamental concepts in psychology that explain how we learn from our environment. Both involve learning associations, but they work in different ways. Classical conditioning is about associating two stimuli (for example, a sound and food) to elicit an automatic response, whereas operant conditioning is about associating a behavior and its consequence (a reward or punishment) to influence whether that behavior happens again. This article explores the differences between these forms of learning, tracing their historical roots with Ivan Pavlov and B.F. Skinner, and provides real-world examples of how they shape human and animal behavior today.

Classical Conditioning: Pavlov’s Accidental Discovery

Classical conditioning was first discovered by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov in the early 1900s. Pavlov wasn’t initially studying learning at all – he was researching digestion in dogs (a line of work that even earned him the 1904 Nobel Prize) when he noticed something curious. His lab dogs would start salivating not only when they tasted food, but even before – for instance, when they saw the lab assistant who usually fed them. This was puzzling because salivation is a reflexive, automatic response to food, not to a person walking into the room.

Intrigued, Pavlov designed a series of experiments to investigate this phenomenon. He began pairing a neutral stimulus (such as a sound) with the presentation of food. In one famous setup, he rang a bell (or in some trials, a metronome) and then immediately gave the dog food. Initially, the bell meant nothing to the dog, but after several repetitions, the dog started to drool simply upon hearing the bell, even if no food followed.

In other words, the dog had learned that the bell predicted food and responded as if food was on the way. Pavlov found that by associating the sound of a bell with the taste of food, dogs would begin to salivate at the sound alone. He called this learned anticipation a “conditioned reflex.” The previously neutral bell became a conditioned stimulus that evoked a conditioned response (salivation), illustrating what we now call classical conditioning.

Pavlov’s findings were groundbreaking. They revealed that organisms can learn by association: if one stimulus reliably precedes another, a subject can begin to respond to the first as if it were the second. This form of learning turned out to apply not just to dogs, but to many organisms – including humans. For example, psychologist John B. Watson famously showed that emotional reactions could be conditioned in people.

In a 1920 experiment, little Albert (an infant in Watson’s study) initially had no fear of a white rat. Watson and his colleague Rosalie Rayner then repeatedly made a loud, frightening noise each time the baby saw the rat. After a few such pairings, the child began to cry just upon seeing the white rat, even without the noise. He had learned to associate the rat with the scary noise, demonstrating that even fears and other emotions can be acquired through classical conditioning. This explains how a harmless thing can come to trigger fear or other feelings – for instance, someone might develop a phobia of dogs after being bitten once, because they start associating the sight of dogs with the pain and fear of the bite.

Everyday Examples of Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning often happens in our daily lives without us realizing it. Have you ever felt nervous just sitting in a dentist’s waiting room because you associate it with the pain of past procedures? That’s classical conditioning at work – the waiting room is a neutral place, but through association with unpleasant dental work it becomes a trigger for anxiety.

Similarly, certain smells or songs can evoke vivid memories and feelings. For example, the smell of chlorine might instantly take you back to happy summers at the pool, or a particular song might make you feel nostalgic because it was playing during a meaningful event in your life. Advertisers also take advantage of classical conditioning: a commercial might pair a product with upbeat music or attractive imagery so that we come to feel positive about the product (the previously neutral stimulus) by association. In all these cases, we respond involuntarily with feelings or reflexes that we’ve learned to associate with something else.

Operant Conditioning: Skinner’s Behavior Shaping

If classical conditioning is about involuntary responses (like reflexes or emotions) triggered by new cues, operant conditioning is about voluntary behaviors and their consequences. This concept was developed by American psychologist B.F. Skinner, who expanded on earlier ideas from Edward Thorndike. Thorndike had formulated the law of effect – the observation that behaviors followed by satisfying outcomes are more likely to be repeated, while those followed by unpleasant outcomes are less likely to be repeated.

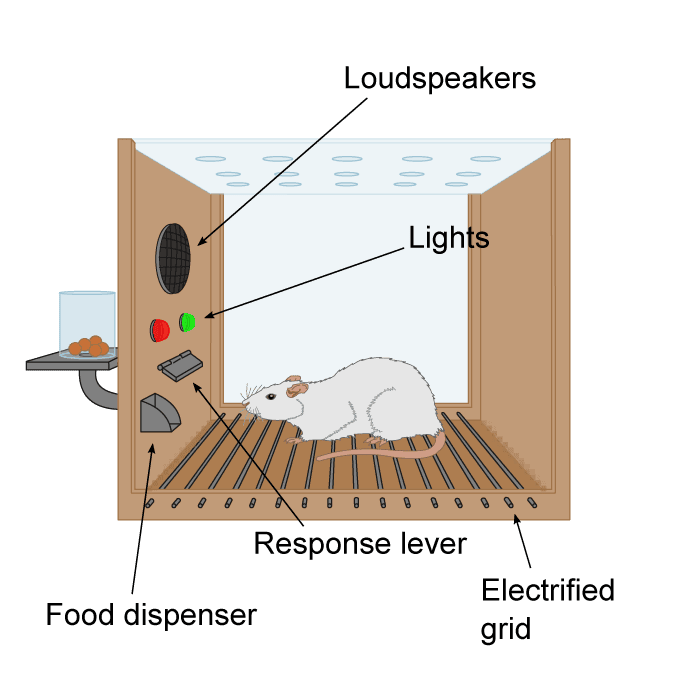

Skinner took this idea and ran with it. He believed that most of our behaviors are influenced by the consequences that follow them. In the 1930s, Skinner began scientifically testing how consequences shape behavior by conducting experiments with animals, mainly rats and pigeons. He built an apparatus called the Skinner box (operant conditioning chamber) – essentially a small box equipped with a lever or button, a food dispenser, and sometimes lights or sounds. When the animal inside presses the lever (a voluntary action), it can receive a food pellet reward. Skinner would observe how changing the consequences (giving a reward, not giving it, or even administering a mild punishment like a slight shock) affected the animal’s behavior.

The core idea of operant conditioning is simple but powerful: behaviors that are reinforced tend to increase, while behaviors that are punished tend to decrease. Reinforcement means the consequence makes the behavior more likely in the future – this could be giving something positive (called positive reinforcement, like a treat or praise) or removing something negative (called negative reinforcement, like stopping a loud noise when the animal does the right thing).

Punishment is the opposite – it makes the behavior less likely to occur again, either by adding an unpleasant outcome (positive punishment, like a scolding or shock) or taking away something desirable (negative punishment, like confiscating a toy). Unlike classical conditioning, which links two stimuli, operant conditioning links a behavior with its result. The learner is active, choosing to perform (or not perform) a behavior based on its past consequences.

Skinner’s research showed how remarkably adaptive behavior can be. For instance, a rat that accidentally presses a lever and gets food will press it again, and soon it learns to press the lever whenever it’s hungry. Skinner also worked with pigeons – he could shape their actions by rewarding successive approximations of a target behavior (a process called shaping).

By doing so, he managed to teach pigeons to do surprisingly complex things. In one famous demonstration, Skinner used shaping to train pigeons to play ping-pong – the birds learned to hit a tiny ball back and forth for a food reward! This might sound amusing, but it underscored a serious point: through operant conditioning, even new and non-instinctive behaviors can be learned if reinforced step by step. Animal trainers today still use these principles – whether it’s teaching dogs to fetch or dolphins to do tricks, rewarding incremental successes is key.

Everyday Examples of Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning is constantly at play in everyday life, because much of our behavior is guided by past rewards and punishments. Consider how parents teach young children right from wrong. If a child cleans their room and gets praised or a treat, that positive reinforcement makes it more likely the child will clean up again in the future.

Conversely, if the child hits a sibling and is put in time-out (a form of punishment by removing them from play), that behavior is likely to decrease. In workplaces, operant conditioning is evident when employees work hard to receive bonuses, promotions, or even just a paycheck – as Skinner would say, the salary is reinforcing the behavior of coming to work.

On the flip side, getting a speeding ticket (a punishment) tends to make us drive more cautiously to avoid future fines. Even our personal habits can be shaped this way. For example, if you set a goal to exercise regularly and you reward yourself with a favorite smoothie after each workout, you’re using positive reinforcement to make yourself more motivated to exercise. Over time, the behavior becomes a habit because it’s been consistently rewarded.

Key Differences Between Classical and Operant Conditioning

While both classical and operant conditioning involve learning from experience, they differ in what is being learned and how the learning occurs. Here are some key differences:

- Involuntary vs. Voluntary: Classical conditioning usually involves involuntary, automatic responses (reflexes or emotions). The subject doesn’t need to actively do anything; the response (like salivation or fear) just happens after the stimulus. Operant conditioning involves voluntary behaviors – the subject chooses to act in a certain way (pressing a lever, cleaning a room) to obtain a reward or avoid punishment. In classical conditioning the organism is more passive (learning by association), whereas in operant conditioning the organism is active (learning by doing).

- What’s Being Associated: In classical conditioning, an organism learns an association between two stimuli – one stimulus (like a bell) comes to predict another stimulus (like food). The learned behavior is a reflex triggered by the first stimulus. In operant conditioning, the association is between a behavior and its consequence – the organism learns that a certain action will result in a certain outcome (reward or punishment). Rather than triggering an existing reflex, operant conditioning leads to new behaviors or changes in the frequency of behaviors based on outcomes.

- Timing: In classical conditioning, the neutral stimulus typically occurs just before the unconditioned stimulus (the bell rings before the food arrives) so that the organism comes to expect the second stimulus after the first. In operant conditioning, the reinforcement or punishment comes after the behavior, as a consequence of it. Essentially, classical conditioning is about what happens before a reflex, whereas operant conditioning is about what happens after a voluntary action.

- Extinction: Both types of learning can fade if the associations stop. In classical conditioning, if the conditioned stimulus (e.g. bell) is presented many times without the unconditioned stimulus (food), eventually the learned response (salivation) will diminish – a process called extinction. In operant conditioning, if a behavior that was reinforced stops being reinforced, the behavior will gradually stop as well. For example, if a slot machine stops paying out (no more reward), a person will eventually quit playing.

Despite these differences, it’s important to note that classical and operant conditioning aren’t mutually exclusive – both processes can be occurring in the same situation. For instance, consider a pet dog: it may learn to come running at the sound of a crinkling treat bag (classical conditioning, associating a sound with food) and also learn to sit on command because it gets a treat when it does so (operant conditioning, performing a behavior for a reward).

Why These Forms of Learning Matter Today

Understanding classical and operant conditioning isn’t just a theoretical exercise from old psychology textbooks – these principles have many practical applications in modern life. Therapists use classical conditioning principles to help people overcome phobias by gradually associating the feared object with calm, safe experiences (a technique known as desensitization). Classical conditioning also plays a role in treating disorders like PTSD and addiction, by breaking associations that trigger harmful reactions.

Operant conditioning principles are widely used in education and parenting, under the banner of behavior modification – for example, teachers might use token reward systems to encourage participation and good behavior in class, and parents use praise (or time-outs) to guide their children’s actions. Animal training, as mentioned, relies heavily on operant conditioning: from guide dogs learning to aid people with disabilities to dolphins learning rescue tasks, reward-based training is the norm. Even our personal self-improvement efforts (like sticking to an exercise routine or productive schedule) often succeed or fail based on how we reward or discipline ourselves.

In summary, classical conditioning (pioneered by Pavlov) teaches us how creatures can form associations between events and thus anticipate what’s coming, while operant conditioning (championed by Skinner) teaches us how outcomes shape future actions. These two forms of conditioning provide a foundation for understanding a huge range of behaviors.

From a dog salivating at the sound of a bell to a student studying hard to earn good grades, the principles discovered by Pavlov and Skinner continue to influence both psychology as a science and the everyday techniques we use to train, teach, and even manipulate behavior. By recognizing these conditioning processes in daily life, we become more aware of how experiences shape our reactions and habits – and that awareness is the first step in learning how to change them if we need to.