A new study published in Environment and Behavior suggests that communities with more green vegetation may experience fewer fatal police shootings. Analyzing data from over 3,000 counties in the contiguous United States, the researchers found that counties with higher levels of greenness had lower rates of police killings. This relationship was even stronger in highly urbanized and socially deprived areas.

Green space, often referred to as “greenness,” includes vegetation such as trees, lawns, and parkland. While previous research has linked green environments to improved mental health, lower crime rates, and reduced stress, little was known about how greenness might relate to deadly encounters with police. With police shootings representing a major public health and social justice issue in the United States, the researchers sought to explore whether the physical environment—specifically the presence of green space—could play a role in shaping these outcomes.

The study was conducted by a team of researchers at the University of Hong Kong, led by Associate Professor Bin Jiang and his PhD student Jiali Li. Their motivation stemmed from the persistent media coverage of fatal police shootings and a scientific interest in whether the natural environment could buffer against violence. Drawing on well-established evidence that green space reduces stress and promotes social cohesion, the team set out to test the link between vegetation levels and fatal police shootings on a national scale.

“The Urban Environments and Human Health Lab at the University of Hong Kong conducted this study with enormous support from Professor Sullivan and Professor Browning,” explained Jiang, founding director of the lab, program director of the Master of Landscape Architecture program, and co-author of the upcoming book https://amzn.to/43vzs0s.

“The major inspiration came from the repetitive reports of fatal police shooting cases by the media. As researchers and practitioners in the field of environmental health, we had an instinct that the provision of green spaces in different areas might play a role. This instinct was based on our knowledge of theories and scientific evidence reported by many previous studies on the relationship between green space exposure and psychological and behavioral health.”

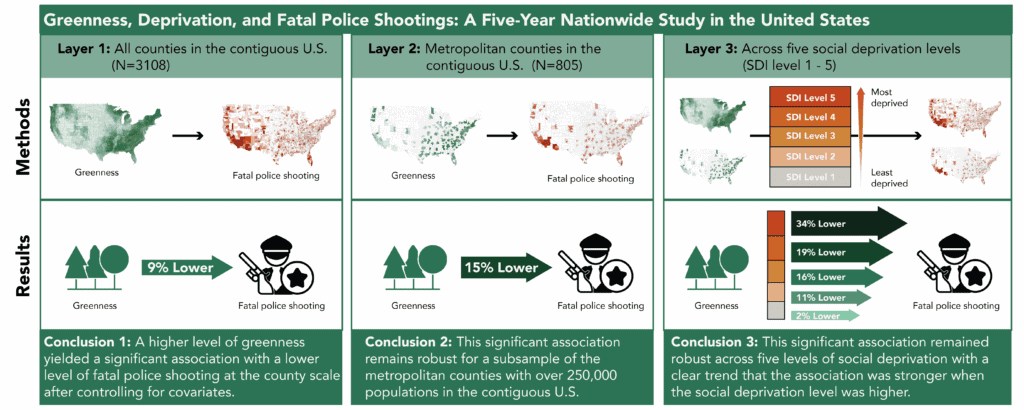

To investigate this question, the researchers analyzed fatal police shootings that occurred between 2016 and 2020 across 3,108 counties in the contiguous United States. They focused only on shootings that resulted in death, drawing from three major open-source databases: Mapping Police Violence, Fatal Encounters, and The Washington Post’s Fatal Force database. These sources collectively captured over 5,000 fatal police shootings during the study period.

To measure greenness, the team used satellite data from Landsat 8, which allowed them to calculate a vegetation index known as NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index). This index reflects the amount of healthy vegetation in an area. They computed annual greenness levels for each county using satellite images from four different seasons.

The study also accounted for a wide range of other factors that might influence police shootings. These included demographic and economic characteristics, violent crime rates, gun laws, firearm ownership, mobility patterns, racial segregation, and levels of urban development. The researchers used a statistical model known as the Besag-York-Mollié (BYM) model to account for both spatial clustering and non-spatial differences across counties.

Their analysis revealed a consistent pattern: higher levels of greenness were associated with fewer fatal police shootings. Across all counties, a one-unit increase in the greenness index was linked to a 9% decrease in fatal police shootings. In urban counties with populations over 250,000, the association was even stronger—a one-unit increase in greenness was linked to a 15% reduction in police killings. Importantly, this negative association held true even after adjusting for crime rates, population density, and socioeconomic indicators.

“To our best knowledge, this is the first study to report a significant relationship between fatal police shootings and the level of greenness,” Jiang told PsyPost. “The relationship remains robust after controlling for a large number of confounding factors, which suggests that the quantity and quality of the landscape matter for achieving safer neighborhoods and regions. Controlling for confounding factors is critical, as many citizens often think such an association is a coincidence. In this study, we found the relationship is independent of race, income, population density, the Gini index, gender, age, unemployment rate, and many other factors.”

The researchers also found that the association between greenness and police shootings varied by the level of social deprivation in a county. In areas with higher levels of deprivation—measured using a Social Deprivation Index—the protective effect of green space was stronger. Counties with the highest levels of deprivation experienced the most pronounced reduction in fatal police shootings associated with higher greenness levels.

“A special and critical contribution of this study is that we found the negative association between fatal police shootings and green landscapes became stronger as the level of social deprivation increased,” Jiang explained. “Past studies have not investigated this relationship from this perspective. Moreover, we found the negative association was stronger for metropolitan counties than for non-metropolitan counties, which suggests the effects of green landscapes may be greater in more urbanized regions.”

The authors offered several explanations for these findings. One possibility is that green spaces reduce stress, anxiety, and mental fatigue—both for residents and potentially for police officers—making aggressive interactions less likely. Green surroundings may also give the impression that a neighborhood is more cared for and less dangerous, which could influence how officers perceive risk during encounters. Additionally, green spaces often encourage social interaction and community cohesion, which may enhance informal social control and reduce tensions that lead to police involvement.

“It may be surprising for many people to see our findings,” Jiang said. “However, many previous studies in the fields of environmental psychology and environmental behavior suggest that greener neighborhoods and cities can facilitate positive emotions, mental relaxation, social trust, social support, and natural surveillance among residents.”

“In contrast, barren neighborhoods and cities can stimulate suspicion, anger, frustration, a sense of unsafety, violent behaviors, deviant behaviors, and many other negative mental states and actions. Our findings are strong and reasonable. However, this is a fresh message for society because the impacts of green landscapes on fatal police shootings have not been well investigated before.”

While the findings are striking, the authors caution that the results are correlational. The study does not prove that increasing green space directly reduces police shootings. Even though the researchers controlled for many variables, other unmeasured factors could still contribute to the association. In addition, the data relied on existing open-source records of police shootings, which may be incomplete or inconsistently reported across jurisdictions.

Despite these limitations, the researchers argue that their findings support a broader perspective on community safety. Rather than focusing solely on policing reforms or crime deterrence, policymakers might also consider how the physical environment shapes safety and well-being.

“Green space is only one of many factors that can contribute to reducing fatal police shootings,” Jiang told PsyPost. “People may criticize: ‘Why does your research focus on a less important factor? You should investigate more important issues like income and education!’ My response is that, as researchers in the field of environmental health, my team and I are using our expertise to inform society and government of the unique and significant benefits of green spaces. We are not neglecting other important factors. On the contrary, we hope all relevant disciplines will join in researching this critical issue and work together to address the problem from many different pathways.”

Investments in green infrastructure—such as planting trees, creating parks, or greening vacant lots—could be a relatively low-cost strategy to help reduce violence and improve public health, especially in underserved communities.

“Provide more green spaces and reduce barren spaces,” Jiang said. “The spaces should be green and functional. They can facilitate positive social interactions and recreational activities, which could further contribute to better social cohesion and trust among residents, authorities, and other stakeholders.”

“The green landscapes should be well designed and maintained by local governments and communities in a variety of ways so that more green spaces can be created and sustained in deprived areas at low cost. It is critical to avoid making green spaces only for affluent people and to provide equal access to green spaces for all population groups in order to avoid gentrification.”

“In socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, adding functional green spaces may be an effective way to reduce fatal police shootings and other forms of violence,” Jiang continued. “Green space can act as a catalyst to stimulate better psychological states and behaviors for everyone.”

Looking ahead, the researchers plan to examine the specific types of green space that matter most—such as parks versus street trees—and assess how people perceive and interact with these environments. Natural experiments or urban interventions could also help determine whether increasing greenness directly leads to meaningful reductions in police shootings and other forms of violence.

The study, “Greenness, Deprivation, and Fatal Police Shootings: A Five-Year Nationwide Study in the United States,” was authored by Jiali Li, Matthew E. Browning, William C. Sullivan, Xueming Liu, and Bin Jiang.