In 1884, while attempting to define the limits of human perception, Charles Pierce and Joseph Jastrow discovered something else: the limits of our insight into ourselves.

Participants in their experiments systematically under-rated their ability to correctly judge their own sensations, which Pierce and Jastrow offered as an explanation of “the insight of females as well as certain ‘telepathic’ phenomena”. These particular implications have thankfully been left behind (along with the conceptual relationship between telepathy and female insight). But by the late 1970s this approach of asking participants to rate their own performance had emerged as its own field of research: the study of “metacognition”.

Broadly, this ability to self-reflect and think about our own thoughts allows us to feel more or less confident in our decisions: we can act decisively when we’re confident we are correct, or be more cautious after we feel we’ve made an error.

This affects all aspects of our behaviour, from long-term abstract influences such as defining our life goals, to the basic influences of judging our own sensations (what we see, hear, smell, taste, and touch).

We aren’t always good at metacognition. Some people are in general over-confident, some are under-confident and most people will occasionally feel very confident about a bad choice.

Metacognition is known to develop through childhood and adolescence, and poor metacognition has been implicated in several psychiatric disorders.

It’s clear that we need to develop educational tools and treatments to improve metacognition. But we are still far from fully understanding how it works.

How should the brain look at itself?

In order to think about your own thoughts, your brain effectively has to look at itself.

In theory, any time some of the hundreds of billions of cells in the brain get together and achieve a thought, feeling, or action, they also report how well they did it. All brain processes are monitored and evaluated, which gives rise to metacognition. One of the big questions is: how?

In our lab we study metacognition in its most basic form, our ability to judge our own sensations.

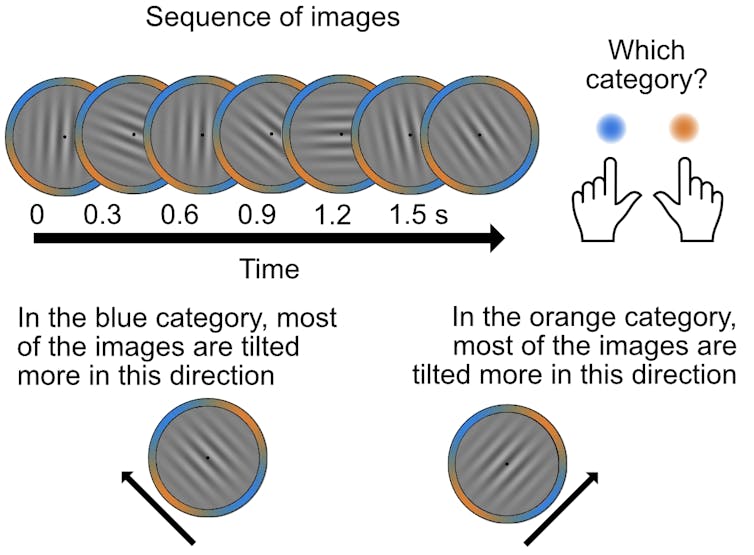

We still use similar methods to Pierce and Jastrow. In a typical experiment, we will show participants an image and ask them to make a simple decision about what they see, then rate how confident they are that they made the correct choice. As a simple example, we could show them an almost vertical line and ask them to judge whether it is tilted to the left or right. The participant should feel more confident when they feel they do not need to look back at the line to check that they’ve made the correct choice.

We call this “decision evidence”. Just like in a court a jury will decide if there is enough evidence to convict a criminal, the brain decides if there is enough evidence to be confident in a choice.

This is actually a big problem for studying what happens in the brain when people feel more compared to less confident, because a difference in confidence is also a difference in decision evidence. If we find a difference in brain activity between high vs low confidence, this could actually be due to more vs less evidence (the line is perceived more vs less tilted).

We need to separate the brain activity is related to the process of judging the tilt of the line from the brain activity related to feeling confident in judging that tilt.

Separating confidence from decision evidence

We recently found a way to distinguish between these processes, by separating them in time. In the experiment, we measured participants’ brain activity as they made decisions about a whole sequence of images shown one after the other.

We were able to see what happens in the brain as participants viewed the images and came to their decision. Sometimes, participants committed to their decision before all of the images had been shown. In this case, we saw the activity related to making the decision come to a halt. But some activity continued.

Even though participants made their decision early, they still checked the additional images and used them to rate their confidence. In these cases, the brain activity for making the decision is finished, so it can’t get mixed up with the activity related to confidence.

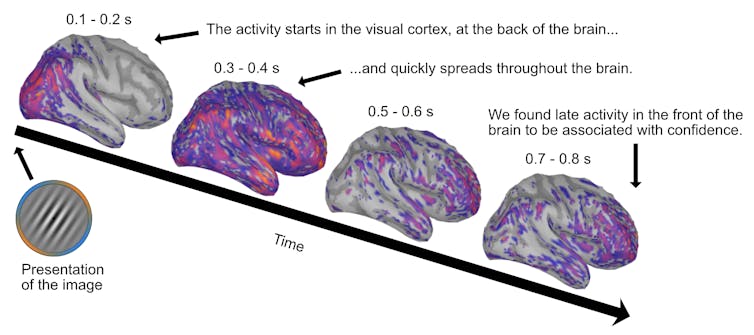

Our first finding agreed with a lot of previous research: we found activity related to confidence in the areas of the brain that are also associated with goal-driven behaviour.

But in closely examining this brain activity, trying to address the question of how the brain looks at itself, we came across a different question: when?

Extreme micro-management

The default view of metacognition is that you make your decision first, then you check how much evidence you have to feel confident – first you think, then you think about thinking. But when we examined the pattern of brain activity related to confidence, we found it evolved even before participants made their decision.

This is like counting your chickens before they’ve hatched. The brain is the most efficient computer we know of, so it’s odd to think it would do something so unnecessary.

The default view suggests a large role of metacognition in moderating future behaviour: our subsequent actions are influenced by how confident we are in our decisions, thoughts, and feelings, and we use low confidence to learn and improve in the future.

But there’s an additional possibility: we could use confidence while we deliberate to know if we should seek out more evidence or if we have enough to commit to a decision.

In a separate experiment, we indeed found that people who are better at metacognition are also better at knowing when to stop deliberating and commit to a decision. This indicates that the brain could be continuously looking at itself, monitoring and evaluating its processes in order to control its efficiency; a system of extreme micro-management.

More than 130 years after Pierce and Jastrow first questioned the role of metacognition we are still discovering new ways this kind of self-reflection is important. In doing so, we are also discovering more about the brain and its amazing ability to look at itself.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.