As a species, humans like to think that we are fully in control of our decisions and behavior. But just below the surface, forces beyond our conscious control influence how we think and behave: our genes.

Since the 1950s, scientists have been studying the influences genes have on human health. This has led medical professionals, researchers and policymakers to advocate for the use of precision medicine to personalize diagnosis and treatment of diseases, leading to quicker improvements to patient well-being.

But the influence of genes on psychology has been overlooked.

My research addresses how genes influence human psychology and behavior. Here are some specific ways psychologists can use genetic conflict theory to better understand human behavior – and potentially advance the treatment of psychological issues.

What do genes have to do with it?

Genetic conflict theory proposes that though our genes blend together to make us who we are, they retain markers indicating whether they came from mom or dad. These markers cause the genes to either cooperate or fight with one another as we grow and develop. Research in genetic conflict primarily focuses on pregnancy, since this is one of the few times in human development when the influence of different sets of genes can be clearly observed in one individual.

Typically, maternal and paternal genes have different ideal strategies for growth and development. While genes from mom and dad ultimately find ways to cooperate with one another that result in normal growth and development, these genes benefit by nudging fetal development to be slightly more in line with what’s optimal for the parent they come from. Genes from mom try to keep mom healthy and with enough resources left for another pregnancy, while genes from dad benefit from the fetus taking all of mom’s resources for itself.

When genes are not able to compromise, however, this can result in undesirable outcomes such as physical and mental deficits for the baby or even miscarriage.

While genetic conflict is a normal occurrence, its influence has largely been overlooked in psychology. One reason is because researchers assume that genetic cooperation is necessary for the health and well-being of the individual. Another reason is because most human traits are controlled by many genes. For example, height is determined by a combination of 10,000 genetic variants, and skin color is determined by more than 150 genes.

The complex nature of psychology and behavior makes it hard to pinpoint the unique influence of a single gene, let alone which parent it came from. Take, for example, depression. Not only is the likelihood of developing depression influenced by 200 different genes, it is also affected by environmental inputs such as childhood maltreatment and stressful life events. Researchers have also studied similar complex interactions for stress- and anxiety-related disorders.

Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes

When researchers study genetic conflict, they have typically focused on its link to disease, unintentionally documenting the influence of genetic conflict on psychology.

Specifically, researchers have studied how extreme instances of genetic conflict – such as when the influence of one set of parental genes is fully expressed while the other set is completely silenced – are associated with changes in behavior by studying people who have Prader-Willi syndrome and Angelman syndrome.

Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes are rare genetic disorders affecting about 1 in 10,000 to 30,000 and 1 in 12,000 to 20,000 people around the world, respectively. There is currently no long-term treatment available for either condition.

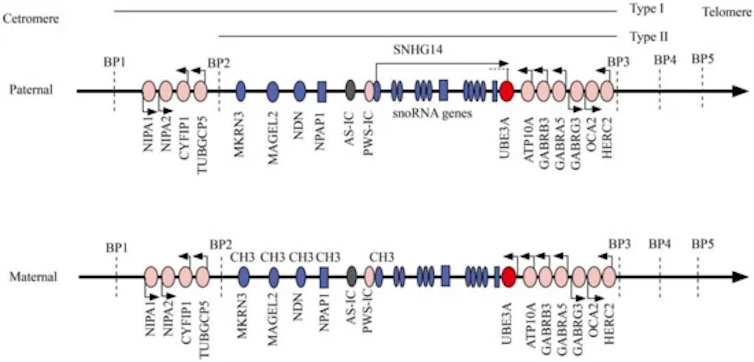

These syndromes develop in patients missing one copy of a gene on chromosome 15 that is needed for balanced growth and development. Someone who inherits only the version of the gene from their dad will develop Angelman syndrome, while someone who has only the version of the gene from their mom will develop Prader-Willi syndrome.

Physical hallmarks of Angelman syndrome include major developmental delays, intellectual disabilities, trouble moving, trouble eating and excessive smiling. Physical hallmarks of Prader-Willi syndrome include diminished muscle tone, feeding difficulties, hormone deficiencies, short stature and extreme overeating in childhood.

These syndromes represent one of the few instances where the influence of a single missing gene can be clearly observed. While both Angelman and Prader-Willi syndromes are associated with language, cognitive, eating and sleeping issues, they are also associated with clear differences in psychology and behavior.

For example, children with Angelman syndrome smile, laugh and generally want to engage in social interactions. These behaviors are associated with an increased ability to gain resources and investment from those around them.

Children with Prader-Willi syndrome, on the other hand, experience tantrums, anxiety and have difficulties in social situations. These behaviors are associated with increased hardships on mothers early in the individual’s life, potentially delaying when their mother will have another child. This would therefore increase the child’s access to resources such as food and parental attention.

Genetic conflict in psychology and behavior

Angelman syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome highlight the importance of investigating genetic conflict’s influence on psychology and behavior. Researchers have documented differences in temperament, sociability, mental health and attachment in these disorders.

The differences in the psychological processes between these syndromes are similar to the proposed effects of genetic conflict. Genetic conflict influences attachment by determining the responsiveness and sensitivity of the parent-child relationship through differences in behavior and resource needs. This relationship begins forming while the child is still in utero and helps calibrate how reactive they will be to different social situations. While this calibration of responses starts at a purely biological level in the womb, it results in unique patterns of social behaviors that influence everything from how we handle stress to our personalities.

Since most scientists don’t consider the influence of genetic conflict on human behavior, much of this research is still theoretical. Researchers have had to find similarities across disciplines to see how the biological process of genetic conflict influences psychological processes. Research on Angelman and Prader-Willi syndromes is only one example of how integrating a genetic conflict framework into psychological research can provide researchers an avenue to study how our biology makes us uniquely human.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.